Welcome! I am Professor of Cultural Evolution at the University of Exeter’s Penryn Campus in Cornwall, UK. I am also Past President of the Cultural Evolution Society.

I study human cultural evolution. I am interested in how human culture evolved, and how culture itself evolves over time.

I use experiments to simulate cultural evolution in the lab. I get people to make and copy technological artifacts like arrowheads or handaxes, or solve problems resembling real-world challenges. The aim is to understand how psychological and social processes have shaped cultural change past and present.

I construct models of cultural evolution. These explore how individual decisions (e.g. when and from whom people learn) translate into population-level patterns of cultural change. I have modeled cumulative technological change, copycat suicides, and the effects of migration on cultural diversity.

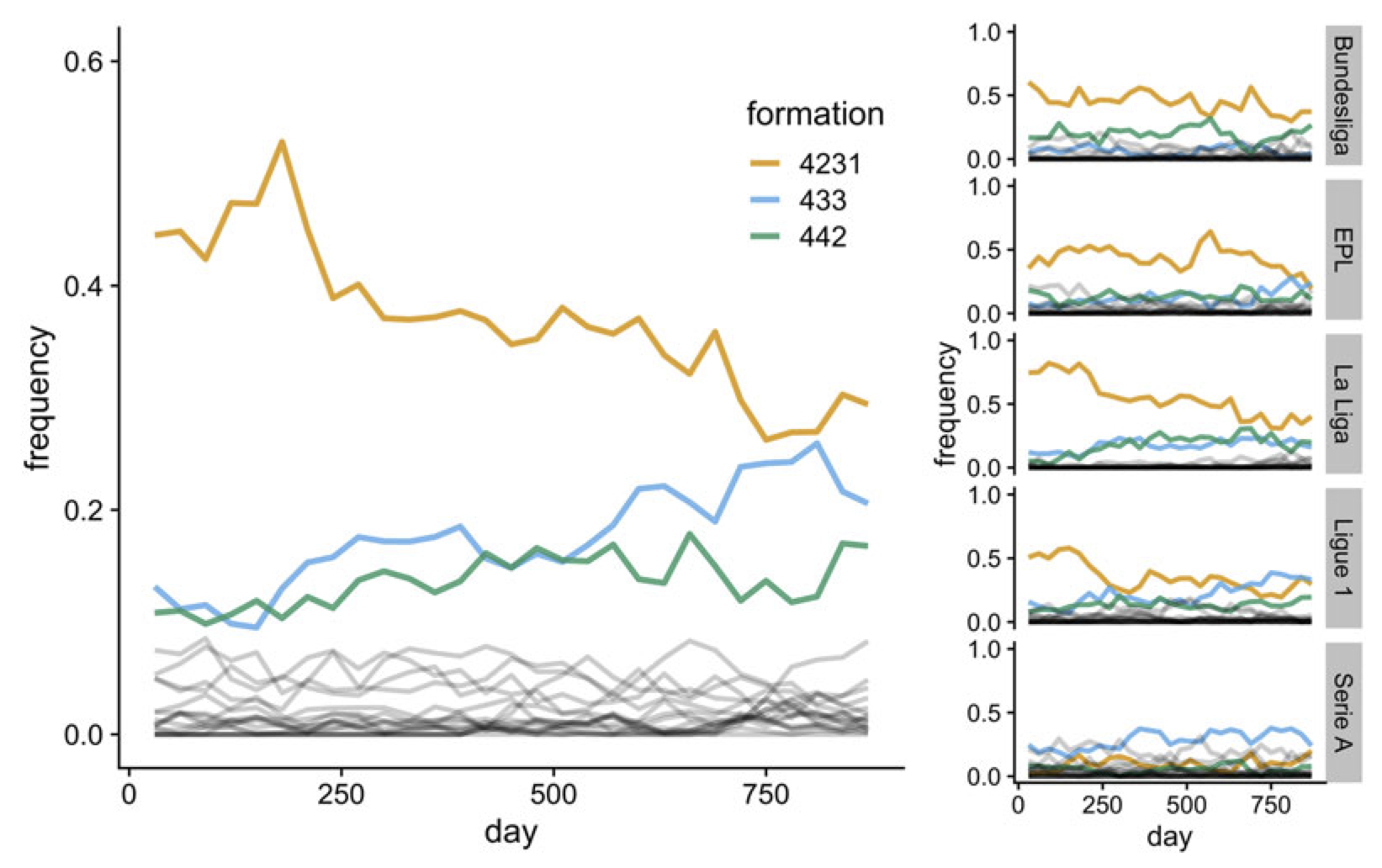

I analyse big datasets to explain real world patterns of cultural evolution. Recent analyses have explored the cultural evolution of pop music, football tactics and nature documentary tweets.

You can read more on the Research page below, or view my Publications here or on Google Scholar.

Contact:

Centre for Ecology and Conservation

University of Exeter, Cornwall Campus

Penryn, TR10 9FE, United Kingdom

Email: a.mesoudi “at sign” exeter.ac.uk

1. Cultural Evolution

The human species has an extraordinary reliance on culture, i.e. the vast body of beliefs, knowledge and skills that we acquire from other individuals via social learning. While other species adapt to their environments primarily via genetic evolution, we adapt via cultural evolution. I am interested in how this process of cultural evolution works, its similarities and differences to genetic evolution, and how traditional social science findings and topics can be studied within an evolutionary framework.

The human species has an extraordinary reliance on culture, i.e. the vast body of beliefs, knowledge and skills that we acquire from other individuals via social learning. While other species adapt to their environments primarily via genetic evolution, we adapt via cultural evolution. I am interested in how this process of cultural evolution works, its similarities and differences to genetic evolution, and how traditional social science findings and topics can be studied within an evolutionary framework.

Representative publications:

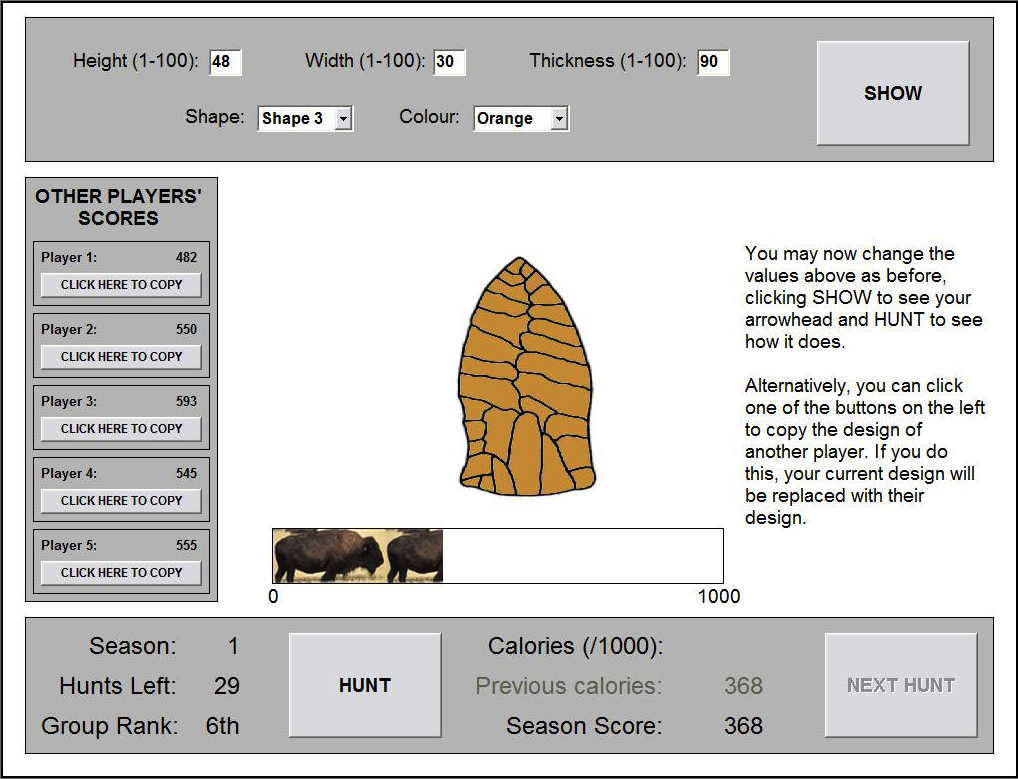

2. Social Learning Experiments

Learning from others, aka 'social learning', lies at the heart of human culture. I have run lab experiments examining how people learn from one another, who they learn from, when they learn from others rather than alone, and what they learn. Some studies use the 'transmission chain method', where stories or task solutions are passed along linear chains of participants like the game 'Telephone'. These have found, for example, that information about social relationships and interactions is transmitted better than non-social information, and that causal understanding is not necessary for improvements in technologies over time. Other studies look at how people within small groups learn from one another over time. Often these experiments look at technological change, getting participants to design arrowheads, handaxes or other objects reflecting real-life human technology. These studies have found that people prefer to learn from successful others, but often copy others less than they should do; and that people copy prestigious people only when direct success information is unavailable.

Learning from others, aka 'social learning', lies at the heart of human culture. I have run lab experiments examining how people learn from one another, who they learn from, when they learn from others rather than alone, and what they learn. Some studies use the 'transmission chain method', where stories or task solutions are passed along linear chains of participants like the game 'Telephone'. These have found, for example, that information about social relationships and interactions is transmitted better than non-social information, and that causal understanding is not necessary for improvements in technologies over time. Other studies look at how people within small groups learn from one another over time. Often these experiments look at technological change, getting participants to design arrowheads, handaxes or other objects reflecting real-life human technology. These studies have found that people prefer to learn from successful others, but often copy others less than they should do; and that people copy prestigious people only when direct success information is unavailable.

Representative publications:

3. Models of Cultural Evolution

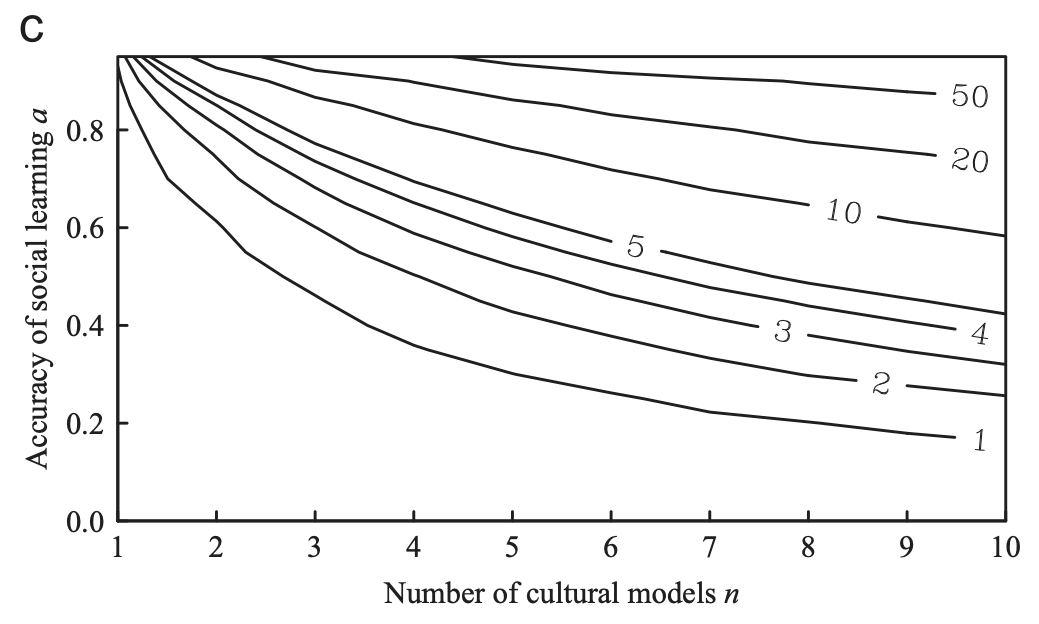

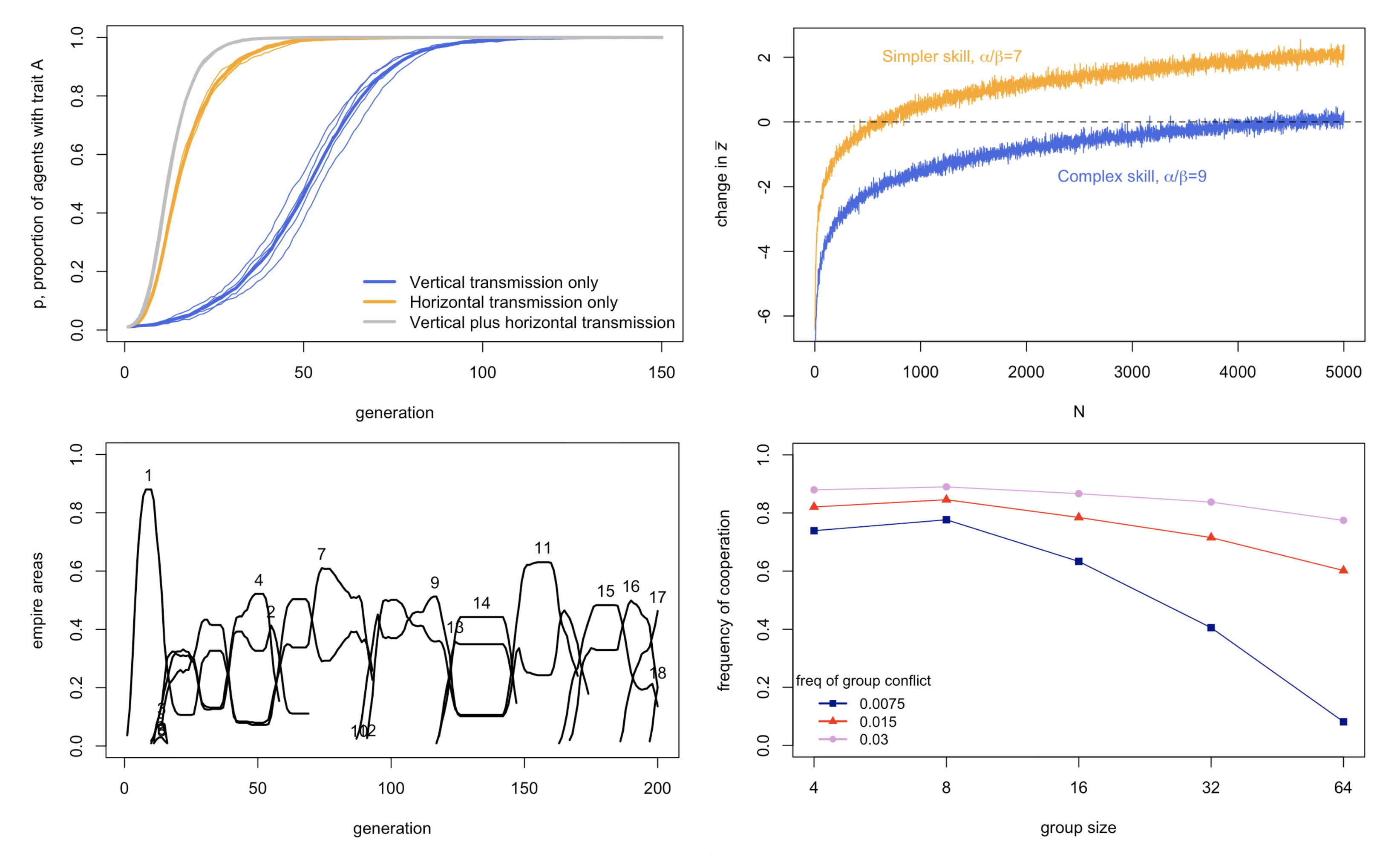

I have used theoretical models, primarily agent-based simulations, to explore how different learning dynamics - who copies what, from whom and when - might generate large-scale patterns of cultural evolution. Previous models have looked at beliefs in partible paternity (where children have more than one biological 'father'), copycat suicide, and how the costs of acquiring ever-accumulating knowledge slows down innovation in cumulative cultural evolution.

I have used theoretical models, primarily agent-based simulations, to explore how different learning dynamics - who copies what, from whom and when - might generate large-scale patterns of cultural evolution. Previous models have looked at beliefs in partible paternity (where children have more than one biological 'father'), copycat suicide, and how the costs of acquiring ever-accumulating knowledge slows down innovation in cumulative cultural evolution.

Representative publications:

Mesoudi (2009) The cultural dynamics of copycat suicide. PLOS ONE 4, e7252.

4. Migration, Acculturation and Cross-Cultural Variation

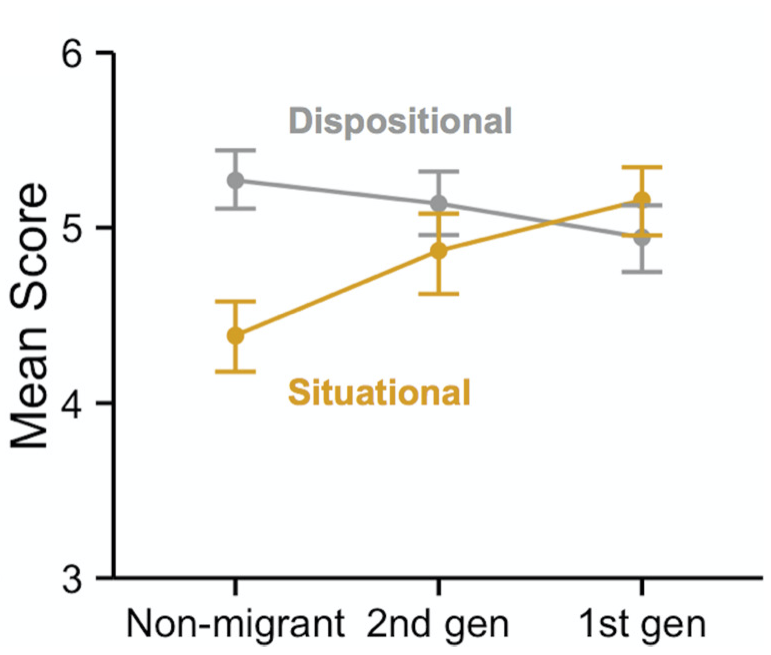

Ever since our species first evolved in Africa, migration has been a constant fixture of Homo sapiens. 'Acculturation' describes the psychological and behavioural changes that occur as a result of migration. I have studied how acculturation affects the psychological characteristics of first and second generation British Bangladeshi migrants in London, and constructed theoretical models showing how acculturation and migration interact to shape cultural diversity over time. Lab experiments have mapped cross-cultural variation in social learning, showing higher rates of social learning in mainland China than in the West.

Ever since our species first evolved in Africa, migration has been a constant fixture of Homo sapiens. 'Acculturation' describes the psychological and behavioural changes that occur as a result of migration. I have studied how acculturation affects the psychological characteristics of first and second generation British Bangladeshi migrants in London, and constructed theoretical models showing how acculturation and migration interact to shape cultural diversity over time. Lab experiments have mapped cross-cultural variation in social learning, showing higher rates of social learning in mainland China than in the West.

Representative publications:

5. Big Cultural Data

The digital age has yielded big cultural datasets that can be used to quantitatively analyse patterns of real-life cultural evolution. Recent projects have analysed and explained large-scale, long-term change in pop music lyrics, football tactics and tweets related to the Netflix documentary Our Planet.

The digital age has yielded big cultural datasets that can be used to quantitatively analyse patterns of real-life cultural evolution. Recent projects have analysed and explained large-scale, long-term change in pop music lyrics, football tactics and tweets related to the Netflix documentary Our Planet.

Representative publications:

Current lab members

- Ishaan Sinha, PhD student, 2023-present

Former postdocs

- Dr Angel V. Jimenez, CES/Templeton funded postdoc, 2023-2024

- Dr Charlotte Brand, Leverhulme Trust funded Postdoctoral Research Associate, 2017-2020

- Dr Maxime Derex, Marie Curie Fellow, 2017-2019 (now holds CNRS position at IAST in Toulouse)

- Dr Kesson Magid, ESRC funded postdoc, 2013-2016 (now at Department of Anthropology, Oxford)

- Dr Delwar Hussain, ESRC funded postdoc, 2013-2014 (now at Department of Anthropology, University of Edinburgh)

- Dr Keelin Murray, ESRC funded postdoc, 2013-2014

Former PhD students

- Dr Andoni Sergiou, PhD student, 2020-2025; passed with minor corrections

- Dr Dugald Foster, University of Exeter, 2019-2023; passed with no corrections

- Dr Angel V. Jimenez, University of Exeter, 2017-2020; passed with minor corrections

- Dr Alice Williams, University of Exeter, 2018-2019 (took over as main supervisor); passed with minor corrections

- Dr Marius Kempe, Queen Mary / Durham University, 2010-2013; passed with minor corrections

- Dr Vera Sarkol, Queen Mary, 2010-2014; passed with minor corrections

Former visiting PhD/MSc students and postdocs

- Dr Wataru Toyokawa, British Academy Visiting Fellow, October-December 2023

- Jérémy Perez, visiting Masters student from Télécom Paris, France, June-August 2021

- Prof André Luiz Borba do Nascimento, visiting PhD student from Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, Brazil, March-August 2017

This tutorial shows how to create very simple simulation or agent-based models of cultural evolution in R. It uses the RStudio notebook or RMarkdown (.Rmd) format, allowing you to execute code as you read the explanatory text. Each model is contained in a separate RMarkdown file which you can open in RStudio. Currently these are:

This tutorial shows how to create very simple simulation or agent-based models of cultural evolution in R. It uses the RStudio notebook or RMarkdown (.Rmd) format, allowing you to execute code as you read the explanatory text. Each model is contained in a separate RMarkdown file which you can open in RStudio. Currently these are:

- Model 1: Unbiased transmission

- Model 2: Unbiased and biased mutation

- Model 3: Biased transmission (direct/content bias)

- Model 4: Biased transmission (indirect bias)

- Model 5: Biased transmission (conformist bias)

- Model 6: Vertical and horizontal transmission

- Model 7: Migration

- Model 8: Blending inheritance

- Model 9: Demography and cultural gain/loss

- Model 10: Polarization

- Model 11: Cultural group selection

- Model 12: Historical dynamics

- Model 13: Social contagion

- Model 14: Social networks

- Model 15: Opinion formation

- Model 16: Bayesian iterated learning

- Model 17: Reinforcement learning

- Model 18: Evolution of social learning

- Model 19: Evolution of social learning strategies

The tutorial is freely available in this github repository. An online version which contains the compiled models with outputs can be found on this bookdown site.

Archaeology Within a Unified Science of Cultural Evolution. Part of the Garrod Research seminar series of the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, 11 January 2024.

A Brief History of Cultural Evolution. Keynote presentation at the Culture Conference 2021: Evolutionary Approaches to Culture, 7th June 2021.

Darwin's Curious Parallel: Towards a Unified Science of Cultural Evolution. Presentation at the National Academy of Sciences Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium on the Extension of Biology Through Culture held at the Beckman Center in Irvine, CA on November 15-16, 2016, organized by Marcus Feldman, Francisco J. Ayala, Andrew Whiten and Kevin Laland.

Towards A Science Of Culture Within A Darwinian Evolutionary Framework. Moderator: Prof. Itamar Even-Zohar. Tel-Aviv, Israel. 2nd June 2015

The Big Picture Science Podcast

Contributor to the episode Post Social Media. 3 June 2024.

Unsupervised Learning podcast

In conversation with Razib Khan. 23 Oct 2022.

This View of Life podcast

Episode entitled "Cultural Evolution with Alex Mesoudi", hosted by David Sloan Wilson. 11 Sep 2020.

The Dissenter podcast

Episode #228 Alex Mesoudi: Studying Cultural Evolution, Migration, And Transmission. 12 Sep 2019.

The Human Zoo

Contributor, Series 8 Episode 4: Democracy and the Wisdom of the Crowds. 12 July 2016.

The Forum Debate: Darwinism and the Social Sciences

Panellist. Organised by the Forum for European Philosophy, London School of Economics. 29 Feb 2016.

Al Jazeera America: Do different generations of immigrants think differently?

Feature/interview on my cross-cultural thinking styles project by novelist Ned Beauman. 24 Feb 2016.